You’re about to quit your job and start living the life of a one-man entrepreneur. Living in your basement, you have no rent and no employees, and since you’re selling your skills you don’t need venture capita yet, but you’re still dreaming big. All things being equal, where should you base your business?

Tip: Probably not in the place where the taxman takes a red bite like this out of your income donut.

More specifically, in each of San Francisco, Helsinki, Sydney, Tokyo and Singapore, if your business earns $100,000 in net revenue and pays you a “ramen-profitable” $2000 monthly net salary:

- How much post-tax profit will your company make in a year?

- If all of this profit is paid out in dividends, how much does will you have left after taxes?

If you’re wondering why I picked those five cities, part of the reason is that it’s a nice geographical, cultural and political spread, but mostly it’s because I’ve either founded a company or worked for a company based in each of them. The $100k net revenue/$2k net salary model, funding product development on the side, is basically what I modeled my one-man consulting company on back in 2006.

To jump straight to the answers, click here. If dividend imputation and municipal inhabitant taxes get you all tingly and excited, read on. Hardcore masochists who’d like to double-check my math are also invited to examine the gruesome innards of this Google Docs spreadsheet.

Disclaimers

This is a hypothetical exercise, so I’m going to simplify as much as I can, the accounting is still stupidly complicated and there’s a whole lot of cramming square pegs into round holes going on. In particular:

- I ignore all non-financial considerations. Visas, availability of talent, infrastructure, economic prospects, legal and political environment etc are all important real-world factors for locating a business, but out of scope for today.

- $100,000 is net revenue, we ignore all expenses aside from salary and tax. In other words, $100,000 is what’s left over after business registration, accounting, stationery and whatnot, and we also assume that those costs are the same across all countries.

- We assume sales tax does not apply. This is not as unfair as it seems, since most countries exempt companies until they reach fairly high yearly sales thresholds and exclude online and/or international/interstate sales.

- The business has no tax deductible expenses. This is particularly unrealistic for the United States, where 72,500 pages of federal tax code means creative deductions are a national pastime, but them’s the breaks.

- Pensions are accounted for on a defined contribution (what-you-pay-is-what-you-get) basis, so $1 put in now is worth (at least) $1 later. This is true for Singapore, Australia, US 401(k)/IRAs and some Japanese corporate plans; this is manifestly not true for US Social Security or the national plans in Finland and Japan, but for lack of a better measure we assume it is anyway.

- Taxes are computed assuming that pension and health insurance contributions are tax-free, which allows me to ignore the distinction between employer and employee contributions.

- The owner is a full-fledged local resident under 40 for the purpose of tax, pension, insurance etc brackets.

- For the sole purpose of minimizing futzing about with exchange rates, for income tax thresholds etc I’m going to merrily assume that 1 USD = 1 SGD = 1 AUD = 1 EUR = 100 JPY. This is obviously not correct, but is not all that much worse than picking actual exchange rates that’ll be out of date in moments anyway.

Last but not least, this is a work in progress, a revision history is at the bottom of the article. Now, let’s roll up our sleeves, channel the spirit of the late great Herbert Kornfeld, and balance this shit wit’ a quickness.

Round 1: Paying a salary

$2000 x 12 = $24,000, leaving $76,000, right? Not so fast. There are four main things to worry about here: income tax, pension fund contributions, payroll taxes and health insurance. Both pensions and health insurance are tricky since our countries’ systems vary so widely, so we’ll just attempt to standardize the legislative minimum. And since all these fees are usually percentages of salary, we have to work our way backwards starting from desired post-tax income to get to the employer’s cost.

In San Francisco, I’m going to cheat a bit and outsource the otherwise horribly complex income tax computation to the MIT Living Wage Survey, which figures that for a single adult, it takes pre-tax earnings of $26,692 to have $1,929/mo left over after tax, an effective tax rate of 13.28%. Optimistically assumes that rate stays the same at $2,000/mo, we now need $27,675. Next, we add in a 6% employee pension contribution with 6% employer matching (+$3203) and boost medical from $149/mo to a post-Obamacare estimate of $368/mo (+$2628). On top of this, employers have to pay 6.2% of wages for Social Security, which I’ll lump as a “pension” for the purposes of this article; 1.45% for Medicare; 3.4% for CA unemployment, plus 1.2% and 0.1% of the first $7,000 only for federal unemployment and employment training tax respectively. (Huge props to ZenPayroll.) In a rare bit of good news, SF’s payroll tax (1.5%) only applies once total salaries exceed $150,000, so we can ignore this. We thus arrive at $36,773.

In San Francisco, I’m going to cheat a bit and outsource the otherwise horribly complex income tax computation to the MIT Living Wage Survey, which figures that for a single adult, it takes pre-tax earnings of $26,692 to have $1,929/mo left over after tax, an effective tax rate of 13.28%. Optimistically assumes that rate stays the same at $2,000/mo, we now need $27,675. Next, we add in a 6% employee pension contribution with 6% employer matching (+$3203) and boost medical from $149/mo to a post-Obamacare estimate of $368/mo (+$2628). On top of this, employers have to pay 6.2% of wages for Social Security, which I’ll lump as a “pension” for the purposes of this article; 1.45% for Medicare; 3.4% for CA unemployment, plus 1.2% and 0.1% of the first $7,000 only for federal unemployment and employment training tax respectively. (Huge props to ZenPayroll.) In a rare bit of good news, SF’s payroll tax (1.5%) only applies once total salaries exceed $150,000, so we can ignore this. We thus arrive at $36,773.

In Helsinki, personal income tax is so complicated the only sane way to compute the effective rate is to punch numbers into the official tax calculator. A gross income of €29,000 and zeroes for everything else, including being a godless pagan who avoids church tax, nets income of €23,978, for an effective rate of 17.32%.

In Helsinki, personal income tax is so complicated the only sane way to compute the effective rate is to punch numbers into the official tax calculator. A gross income of €29,000 and zeroes for everything else, including being a godless pagan who avoids church tax, nets income of €23,978, for an effective rate of 17.32%.

As a >30% shareholder of his own company, our hero can apply the lower “YEL” pension employer contribution of 17.55% for two years. On top of this, we have the employee side pension contribution of 5.15%, 2.04% mandatory health insurance, and 0.80% employer/0.60% employee unemployment insurance. We thus arrive at €36,615, which is, rather incredibly, a hundred bucks less than SF, and this gets you a cradle-to-grave Scandinavian welfare state!

In Tokyo, national income tax (shotokuzei) is 5% for the first Y1.95 million and 10% above, plus a flat 4% prefectural and 6% municipal tax (which combine to form jūminzei, resident tax), which works out to 16.6%. For pension, you can pick the national plan (kokumin nenkin) at a fixed Y14,980/month regardless of income, or a standardized company pension (kōsei nenkin) at 17.120% split evenly between employer and employee; being cheapskates, we pick the national plan. National health insurance is 80% of municipal and prefectural tax paid, which in Tokyo equates to 9.97% split between employer and employee. Phew! (Dōmo arigatō to Japan Consult.) Final damage 33,448 hectoyen, and I’m delighted to find out that I’m apparently the fifth person in the history of the Internet to use that lovably awkward term.

In Tokyo, national income tax (shotokuzei) is 5% for the first Y1.95 million and 10% above, plus a flat 4% prefectural and 6% municipal tax (which combine to form jūminzei, resident tax), which works out to 16.6%. For pension, you can pick the national plan (kokumin nenkin) at a fixed Y14,980/month regardless of income, or a standardized company pension (kōsei nenkin) at 17.120% split evenly between employer and employee; being cheapskates, we pick the national plan. National health insurance is 80% of municipal and prefectural tax paid, which in Tokyo equates to 9.97% split between employer and employee. Phew! (Dōmo arigatō to Japan Consult.) Final damage 33,448 hectoyen, and I’m delighted to find out that I’m apparently the fifth person in the history of the Internet to use that lovably awkward term.

In Sydney, the Tax Office says the first $18,200 of income are tax-free and the next bracket until $37k is 19%, for an effective rate of 5.36%. The minimum pension (superannuation) contribution is 9.25% and Medicare (public health insurance) levy is 1.5%, and since our total income is under $84k, we’re not required to pay the Medicare levy surcharge for not having private insurance. Payroll taxes in Australia are administered at the state level, but New South Wales only applies its rate of 5.45% once payroll exceeds $750,000, so that particular bullet is dodged, and at $28,087, the end result is easily the lowest of the bunch.

In Sydney, the Tax Office says the first $18,200 of income are tax-free and the next bracket until $37k is 19%, for an effective rate of 5.36%. The minimum pension (superannuation) contribution is 9.25% and Medicare (public health insurance) levy is 1.5%, and since our total income is under $84k, we’re not required to pay the Medicare levy surcharge for not having private insurance. Payroll taxes in Australia are administered at the state level, but New South Wales only applies its rate of 5.45% once payroll exceeds $750,000, so that particular bullet is dodged, and at $28,087, the end result is easily the lowest of the bunch.

In Singapore, income tax is easy: 0% for the first $20k, 1.4% for the next $10k (usually 2%, but they’re discounting 30% in 2013), for a scarcely believable effective rate of 0.24%. Mandatory pension (CPF) contributions for employees under 50, which include a health insurance component, are 16% for the employer and the 20% for the employee, with a maximum contribution of $1800/mo (not applicable here). The only other obligatory cost is the Skills Development Levy at 0.25% of salary, capped at $11.25/mo. This equates to $32,777.

In Singapore, income tax is easy: 0% for the first $20k, 1.4% for the next $10k (usually 2%, but they’re discounting 30% in 2013), for a scarcely believable effective rate of 0.24%. Mandatory pension (CPF) contributions for employees under 50, which include a health insurance component, are 16% for the employer and the 20% for the employee, with a maximum contribution of $1800/mo (not applicable here). The only other obligatory cost is the Skills Development Levy at 0.25% of salary, capped at $11.25/mo. This equates to $32,777.

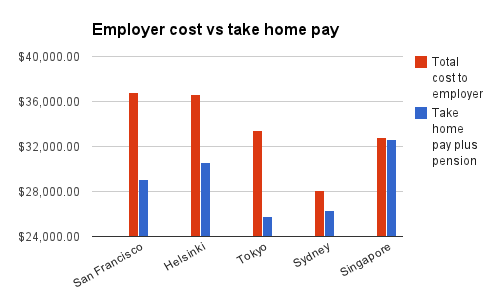

We can now compare the total cost of employment, ie. how much it costs the company to pay the owner that $2000/mo salary:

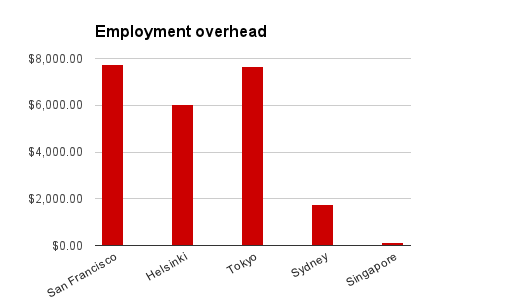

But while taxes disappear into the gaping jaw of Leviathan, pensions are retained by the owner in some form of another (see Disclaimer), so a more instructive comparison deducts salary and pension from total cost to arrive at what I’m calling “employment overhead”:

At the end of Round 1, Singapore is the clear winner ($117!) and Sydney a close second, followed by Helsinki and, at the back of the bus, Tokyo and San Francisco, where nearly $8k disappear in a puff of smoke.

Round 2: Corporate tax and dividend taxation

In our idealized mini-company, everything that was not paid out to the employee is pure profit. If the company wants to dish them out to its sole shareholder, how much do they get after the taxman takes his share?

In California, a C corporation pays 8.84% corporate tax. (A pity we’re not in Nevada, where it would be zero.) Pile on federal taxes at 15% to $50k and 25% to 75k, noting that you can deduct your state corporate tax first, and we get 23.7%. Since California treats dividend income as ordinary taxable income, in the $36k-to-87k tax bracket you’re looking at 25% to Uncle Sam, 12.3% to California, 3.8% to Medicare and 1.2% for “deduction phaseouts” (wat?), totaling a whopping 42.30%. Tot these up, and our entrepreneur is left with 44% of what the company earned, or $27,828. And if that sounds bad, here’s a calculation that arrives at 26% when you max out both tax brackets!

In California, a C corporation pays 8.84% corporate tax. (A pity we’re not in Nevada, where it would be zero.) Pile on federal taxes at 15% to $50k and 25% to 75k, noting that you can deduct your state corporate tax first, and we get 23.7%. Since California treats dividend income as ordinary taxable income, in the $36k-to-87k tax bracket you’re looking at 25% to Uncle Sam, 12.3% to California, 3.8% to Medicare and 1.2% for “deduction phaseouts” (wat?), totaling a whopping 42.30%. Tot these up, and our entrepreneur is left with 44% of what the company earned, or $27,828. And if that sounds bad, here’s a calculation that arrives at 26% when you max out both tax brackets!

That said, if you’re going to do this in real life and do not have ambitions to grow to be the next Google, you should almost certainly opt for an S corporation or an LLC instead. These don’t pay corporate taxes: instead, they pass their income (or loss) onto their shareholders, who then pay normal income taxes. This is good if you’re keeping the money, but terrible if you were planning to reinvest it. However, since all other corporation types in this little survey are “real” companies that can choose to reinvest or issue dividends, I felt that a C corporation is a fairer comparison point.

In Helsinki, both corporate tax and the tax treatment of dividends was revamped in 2013. From January 2014 onwards, corporate tax is 20%, leaving €63,385 in post-tax profits. The basic capital gains tax on dividends is 30% (but 32% above €40k), with a tax break of 75% on the first 8% of “free capital”, which for our newborn company equates to the total yearly profit. This works out to an effective rate of 28.59%, leaving €36,211 in our hero’s bank account.

In Helsinki, both corporate tax and the tax treatment of dividends was revamped in 2013. From January 2014 onwards, corporate tax is 20%, leaving €63,385 in post-tax profits. The basic capital gains tax on dividends is 30% (but 32% above €40k), with a tax break of 75% on the first 8% of “free capital”, which for our newborn company equates to the total yearly profit. This works out to an effective rate of 28.59%, leaving €36,211 in our hero’s bank account.

In Tokyo, corporate taxation makes Japanese payroll and income taxes look simple. Based on this handy summary from JETRO, for “a small company in Tokyo”, corporate tax is 15%, “restoration corporate surtax” (read: Fukushima surcharge) is 1.5%, prefectural and municipal “inhabitant taxes” in Tokyo are 0.75% and 1.85% respectively, “enterprise tax” is 2.70% (I presume this is meant to discourage entrepreneurship?) and as a cherry on top “special local corporate tax” is 2.19%, for a total of 23.99% but an effective rate of 22.86% for reasons I won’t even claim to understand. But wait! Once your earnings top Y4m, new rates apply and you now get socked for 24.56%. In effect, the effectively effective rate is an ineffective 23.54%.

In Tokyo, corporate taxation makes Japanese payroll and income taxes look simple. Based on this handy summary from JETRO, for “a small company in Tokyo”, corporate tax is 15%, “restoration corporate surtax” (read: Fukushima surcharge) is 1.5%, prefectural and municipal “inhabitant taxes” in Tokyo are 0.75% and 1.85% respectively, “enterprise tax” is 2.70% (I presume this is meant to discourage entrepreneurship?) and as a cherry on top “special local corporate tax” is 2.19%, for a total of 23.99% but an effective rate of 22.86% for reasons I won’t even claim to understand. But wait! Once your earnings top Y4m, new rates apply and you now get socked for 24.56%. In effect, the effectively effective rate is an ineffective 23.54%.

So that’s taxes, now dividends, which are even more like tentacle porn. To quote Japan Tax, “As so often seems the case with Japanese individual taxation, what would be expected to be a simple tax matter is made overly complicated by a range of expiring tax benefits (that are often revised or extended) and a range of alternative obscure reporting elections, deductions or exemptions.” The short of it is that the withholding tax rate for unlisted shares is 20%. The long of it is that you can then choose to report or not report it as ordinary income. If you do report, you have to pay income tax, but receive a dividend deduction of 12.8% for overall income of Y10m or less but 6.4% above which offsets the withholding tax and, you know what, fuggedaboudit. Pay 20%, end of story, and keep 40,709 hectoyen.

In Sydney, company tax is a flat 30%, no if ands or buts, and the highest rate in our survey. Dividend income is treated the same as ordinary income and taxed at same rate, except that thanks to dividend imputation you get “franking benefits” that are meant to offset the corporate tax already paid. Acting on the optimistic assumption that they do, this means all that’s left is the difference between the corporate tax rate and the receiver’s marginal income tax rate, in our case 32.5% (for the $37k+ tax bracket) plus 1.5% levy, or 4%. This leaves a rather juicy $48,326.

In Sydney, company tax is a flat 30%, no if ands or buts, and the highest rate in our survey. Dividend income is treated the same as ordinary income and taxed at same rate, except that thanks to dividend imputation you get “franking benefits” that are meant to offset the corporate tax already paid. Acting on the optimistic assumption that they do, this means all that’s left is the difference between the corporate tax rate and the receiver’s marginal income tax rate, in our case 32.5% (for the $37k+ tax bracket) plus 1.5% levy, or 4%. This leaves a rather juicy $48,326.

In Singapore, corporate tax is usually 15%, but new companies in many sectors including IT pay zero (0%) tax for the first three years for their first $100k in profit, no special applications needed. There’s also a whole slew of other tax incentives, including 4x deductions of IT gear and, most incredibly, cash transfers of up to $5,000/year from the tax man for companies that make a loss despite earning over $100,000 in revenue, but that’s another story and our rules exclude this kind of thing anyway.

In Singapore, corporate tax is usually 15%, but new companies in many sectors including IT pay zero (0%) tax for the first three years for their first $100k in profit, no special applications needed. There’s also a whole slew of other tax incentives, including 4x deductions of IT gear and, most incredibly, cash transfers of up to $5,000/year from the tax man for companies that make a loss despite earning over $100,000 in revenue, but that’s another story and our rules exclude this kind of thing anyway.

Singapore has no capital gains tax, so Singapore company dividends are also tax-free. The company can thus pay out $67,223 in dividends, and the shareholder gets every last cent. This means our entrepreneur’s yearly earnings after tax are $91,223, and adding in the $8,640 sitting in their pension fund, they have managed to hold on to $99,883 of it.

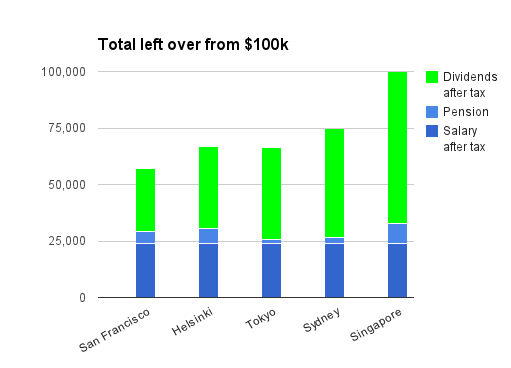

Dear reader, if you made it this far, I salute you. Now all that’s left is to sum up your salary, your pension and what’s left of your dividends to see how much of your $100,000 you still have left over.

Conclusion

Singapore romps home as the undisputed winner, with the entrepreneur keeping a scarcely credible 99.9% of what they started with. It’s just a real shame that, for political reasons, the government has recently gutted the EntrePass scheme and thus made it close to impossible for a foreign one-man entrepreneur to set up shop. (If you’re keen anyway, check out the Singapore Expats “Business in Singapore” forum or drop me a line.)

Somewhat to my own surprise, Sydney rocks up in second place with 74.6% left over. Australia’s not what you’d call a low-tax (much less low-cost) country, but income tax is highly progressive and the dividend franking system means you only pay tax once on dividends, meaning that at low incomes you get to keep most of what you earn. The calculus would change pretty rapidly if you earned $200k and found yourself in the 45% income tax bracket.

Helsinki and Tokyo show up neck and neck in 3rd and 4th place, with 66.8% and 66.5% respectively. Both have heavy taxation of income, payroll, corporate profit and dividends, but no total clangers. (Except Finland’s 24% value-added tax, the exclusion of which makes Helsinki unrealistically rosy, unless you can source all your income from outside the EU.) The canny entrepreneur could nudge up both of those figures: in Tokyo, you’d actually want to pay yourself more salary since income tax is lower than corporate tax, while in Helsinki the reverse applies.

And trailing the pack with barely half left over is poor old San Francisco with 56.9%. Now obviously there’s more to deciding where a company sets up than taxes, because otherwise Silicon Valley would be empty… but unless you really need to be there, from a financial point of view setting up pretty much anywhere else seems to make a whole lot more dollars and cents.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to corporate law ninja Joe & serial entrepreneur Juha for a sanity check of the US, Finland and Japan calculations, Tuomas Talola for corrections to Finnish calculations, and my Singaporean accountant, the infatigable Ms Tan, for clueing me onto this stuff back in the day. If you spot any mistakes, drop me a line.

Incidentally, Joe says that a fairer version of this exercise would model the corporate and personal taxes of each country and then solve for the optimal combination of salary and dividends. Any takers?

Revision history

31 Oct 2013

- Recomputed Finnish income taxes with tax office calculator.

- Adjusted Finnish employer pension to use YEL rate instead of TyEL rate.

- Corrected Japanese pension to pay national pension (kokumin nenkin) only.